What is substance use and addiction?

Many people use substances such as drugs or alcohol to relax, have fun, experiment, or cope with stressors. However, for some people, using substances or engaging in certain behaviours can become problematic and may lead to dependence.

Addiction is a complex process where problematic patterns of substance use or behaviours can interfere with a person’s life. Addiction can be broadly defined as a condition that leads to a compulsive engagement with a stimuli, despite negative consequences.1Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. (December 2009). Substance Use in Canada: Concurrent Disorders. Retrieved from: http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/ccsa-011811-2010.pdf

This can lead to physical and/or psychological dependence. Addictions can be either substance related (such as the problematic use of alcohol or cocaine) or process-related, also known as behavioural addictions (such as gambling or internet addiction).2Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. (2010). Substance Abuse in Canada: Concurrent Disorders. Retrieved from: http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/ccsa-011811-2010.pdf Both can disrupt an individual’s ability to maintain a healthy life, but there are numerous support and intervention options available.

A simple way of understanding and describing addiction is to use the 4Cs approach:

- Craving

- Loss of control of the amount or frequency of use

- Compulsion to use

- Continued substance use despite consequences3 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. (2012). What is Addiction? Retrieved from: http://www.camh.ca/en/hospital/health_information/a_z_mental_health_and_addiction_information/drug-use-addiction/Pages/addiction.aspx

How common is substance use and addiction?

Substance use is quite common on an international scale and statistics vary depending on the substance being consumed. It is estimated that nearly 5% of the world’s population have used an illicit substance, 240 million people around the world use alcohol problematically, and approximately 15 million people use injection drugs.4World Drug Report. (2015). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved from: https://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr2015/World_Drug_Report_2015.pdf

In Canada, it is estimated that approximately 21% of the population (about 6 million people) will meet the criteria for addiction in their lifetime. Alcohol was the most common substance for which people met the criteria for addiction at 18%.5Statistics Canada. (2015). Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders in Canada. Retrieved from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-624-x/2013001/article/11855-eng.htm Canada has one of the highest rates of cannabis use in the world, with more than 40 per cent of Canadians having used cannabis in their lifetime and about 10 per cent having used it in the past year.

While some people may be able to consume substances without resulting in significant harms, some people may experience ongoing substance related problems. In Ontario, it is estimated that approximately 10% of the population use substances problematically. Recently, Ontario has seen a growing trend of harms related to opioid use. Opioids are a class of psychoactive drugs that are often used for pain management. These can include: fentanyl, morphine, heroin, and oxycodone. While opioids are effective for pain relief, and many individuals can use them for short periods of time without concern, this class of drugs has led to harms across the province in recent years, including deaths due to overdose. In 2016 there were 865 deaths due to these substances, equal to an opioid-related overdose death occurring in Ontario every 10 hours.

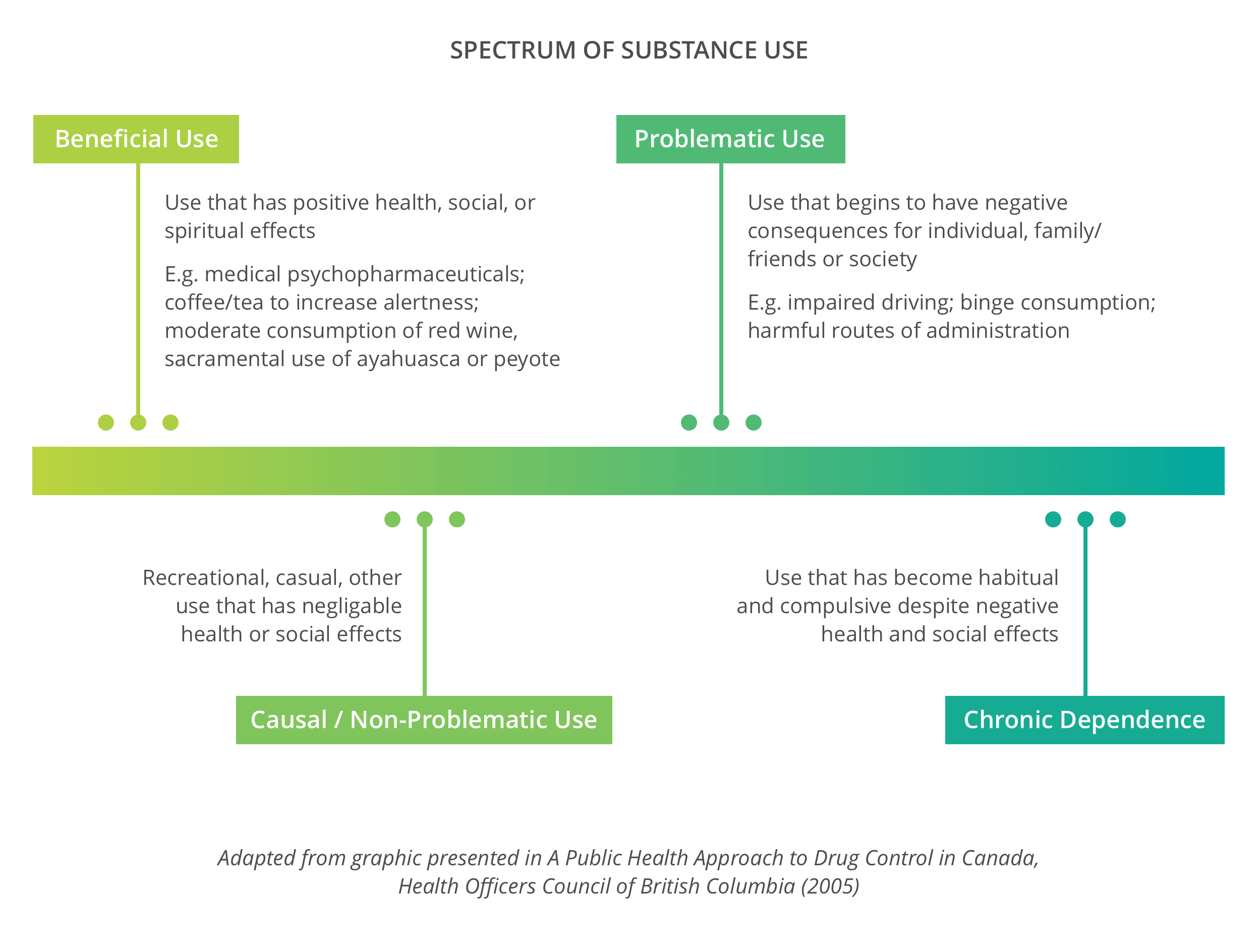

People use substances for different reasons, and in varying degrees. For some people, there may not be any harms related to their substance use. For others, there may be negative impacts on their lives. Substance use and addiction can be understood as being on a spectrum, as seen in the model below.

Often the signs of problematic substance use and addiction can be episodic, and an individual can experience periods of increased substance use as well as periods of control. For example, casual or non-problematic substance consumption might escalate into problematic substance use if an individual is experiencing stressors in their life and is using substances to cope. The substance use spectrum can be seen below:6Health Officers Council of British Columbia. (2005). A Public Health Approach to Drug Control in Canada. Retrieved from: http://www.cfdp.ca/bchoc.pdf

A common misconception about addiction is that an individual will immediately get ‘hooked’ if experimenting with an addictive substance. While many substances can be addictive, addiction isn’t caused simply by the substances being consumed. For example, many people who use opioids for post-operative pain relief do not become dependent on these substances. Addiction and substance use are often connected to a person’s lived experience, mental health and behavior patterns.

Factors that Impact Substance Use and Addiction

The experience of substance use is different for each individual, and often there is a combination of biological, psychological and social factors that can contribute to why a person may be struggling with problematic substance use or addiction. For example, some of the risk factors for addiction include: a person’s genes, the way a person’s brain functions, previous experiences of trauma, cultural influences, or social issues such as poverty and other barriers to accessing the social determinants of health.

An important factor to consider is how mental health and addictions are linked and impact one another. A mental health issue in conjunction with addiction or substance misuse is known as a concurrent disorder. While it is difficult to obtain an accurate statistic of people living with concurrent disorders, research shows that more than 50% of those who are seeking help for a substance use-related issue also face mental health conditions.(European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2013). Models of Addiction. Retrieved from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_213861_EN_TDXD13014ENN.pdf[/fn] Many people who experience addiction or substance use issues also experience stigma and discrimination. Stigma can be defined as a negative stereotype, and discrimination is the behaviour that results from this stereotype.

There are numerous ways that stigma and discrimination can impact a person, such as a loss of self-esteem, a fear of seeking intervention, or feelings of isolation. Often people with concurrent disorders may experience multiple, intersecting layers of discrimination as they are living with both substance use and mental health issues.7Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. (2010). Substance Abuse in Canada: Concurrent Disorders. Retrieved from: http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/ccsa-011811-2010.pdf There is still much to learn about the complexities of substance use and addiction. However, research has indicated that nobody chooses to become addicted to a substance, and that it is not due to a moral failing or weakness with an individual.8Hari, Johann. (2015). Chasing the Scream. The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs. New York: Bloomsbury.

There are some aspects of a person’s life that can contribute to individual becoming less likely to have substance use related issues. These are called protective factors and can include: having a childhood with a positive adult role model, being motivated and having personal goals, involvement in meaningful activities, and being connected to a positive and reliable community of support. As one addiction researcher states “The opposite of addiction is connection.”9Maté, G. (2008). In the realm of hungry ghosts: close encounters with addiction. Toronto: Random House.

Harm Reduction

Harm Reduction is an evidence-based, person-centred approach that seeks to reduce the health and social harms associated with addiction and substance use, without necessarily requiring people who use substances to abstain or stop using.10Thomas, G. (2005) Harm Reduction Policies and Programs Involved for Persons Involved in the Criminal Justice System. Ottawa: Canadian Centre on Substance Use Included in the harm reduction approach to addiction and substance use is a series of programs, services and practices. A harm reduction approach offers people who use substances a choice of how they can minimize harms through non-judgmental and non-coercive strategies. This enhances skills and knowledge on how to live safer and healthier lives.

Harm reduction acknowledges that many individuals coping with addiction and substance use issues may not be in a position to remain abstinent from a substance. The harm reduction approach provides an option for people to engage with medical and social services in a non-judgmental way that will ‘meet them where they are.’11Erickson et. al. (2002) Center for Addiction and Mental Health and Harm Reduction. A Background Paper on its Meaning and Application for Substance use Issues. Retrieved from: http://www.camh.ca/en/hospital/about_camh/influencing_public_policy/public_policy_submissions/harm This allows for a health-oriented response to addiction and substance use, and it has been proven that those who engage in harm reduction services lessen the burden of disease and are more likely to engage in ongoing intervention as a result of accessing these services. Some harm reduction initiatives have also reduced blood-borne illnesses such as HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C, and have decreased the rates of deaths due to drug overdoses.12Pires, R. et. Al. (2007). Engaging users, Reducing Harms. Collaborative Research Exploring the Practices and Results of Harm Reduction. United Way Report. Retrieved from:

What are some examples of harm reduction?

Some practices that take a harm reduction approach include: using a nicotine patch instead of smoking, consuming water while drinking alcohol, using substances in a safe environment with someone they trust, and needle exchange programs for people who inject drugs. Harm reduction doesn’t just apply to the use of substances. We engage in harm reduction in our everyday lives to minimize a risk, such as wearing a helmet when riding a bike or enforcing the use of seat belts when driving in a car.

In order to further understand the philosophy behind Harm Reduction, it is important to discuss the main features, which include:

- Pragmatism: Harm Reduction recognizes that substance use is inevitable in a society and that it is necessary to take a public health-oriented response to minimize potential harms.

- Humane Values: Individual choice is considered, and judgement is not placed on a person who use substances. The dignity of people who use substances is respected.

- Focus on Harms: An individual’s substance use is secondary to the potential harms that may result in that use.13Bierness, D. (2008) Harm Reduction: What’s in a name? Canadian Center on Substance Abuse National Policy Working Group. Retrieved from: http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/ccsa0115302008e.pdf

A frequent misconception of harm reduction is that it supports or encourages illicit substance misuse and does not consider the role of abstinence in addiction intervention. However, harm reduction approaches do not presume a specific outcome, which means that abstinence-based interventions can also fall within the spectrum of harm reduction goals. Essentially, harm reduction supports the idea that those with addiction or substance misuse issues should have a wide selection of intervention options in order to make an informed decision about their individual needs and what would be the most effective for them, while also reducing potential harms.

Substance Use on Campus:14Neilson, A. & Bridgstock, B. (2017). Addressing emerging mental health and addiction needs in post-secondary institutions. Algonquin College Student Support Services. Retrieved from: http://www.addictionsandmentalhealthontario.ca/uploads/1/8/6/3/18638346/hp6_-_addressing_emerging_adult_mental_health___addiction_needs_in_post-secondary_institutions.pdf

- 64 % of those admitted into substance use intervention state that their substance use began during emerging adulthood

- 20 % of substance use intervention admissions occur during emerging adulthood15Smith, J.L. et al. (2014). Deficits in behavioural inhibition in substance abuse and addiction: A meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend, 145:1–33.

16Stanis, J. J. & Andersen, S. L. (2014). Reducing substance use during adolescence: A translational framework for prevention. Psychopharmacology, 231, 1437–1453.

(Smith et al, 2014, Stanis & Anderson, 2014)

Canadian 2016 National College Health Assessment Data:17National College Health Assessment. (Spring 2016). Ontario Canada Reference Group: Executive Summary. Retrieved from: http://oucha.ca/pdf/2016_NCHA-II_WEB_SPRING_2016_ONTARIO_CANADA_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf

- 12.9 % of students used alcohol 10-29 days out of the last 30 days

- 1.0 % of students used alcohol all 30 days

- 3.6 % of students used marijuana 10-29 days out of the last 30 days

- 2.5 % of students used marijuana all 30 days

- 18.1 % of students drove a vehicle after consuming alcohol in the last 30 days

- 35.0 % of students consumed 5 or more drinks in one sitting in the last two weeks

- 11.1 % of students used someone else’s prescription drugs in the last 12 months

- 1.3 % of students were diagnosed or treated for substance use or addiction in the past 12 months

(Canadian NCHA data, 2016 – 41 institutions & 43,780 students)

| ↑1 | Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. (December 2009). Substance Use in Canada: Concurrent Disorders. Retrieved from: http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/ccsa-011811-2010.pdf |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑7 | Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. (2010). Substance Abuse in Canada: Concurrent Disorders. Retrieved from: http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/ccsa-011811-2010.pdf |

| ↑3 | Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. (2012). What is Addiction? Retrieved from: http://www.camh.ca/en/hospital/health_information/a_z_mental_health_and_addiction_information/drug-use-addiction/Pages/addiction.aspx |

| ↑4 | World Drug Report. (2015). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved from: https://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr2015/World_Drug_Report_2015.pdf |

| ↑5 | Statistics Canada. (2015). Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders in Canada. Retrieved from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-624-x/2013001/article/11855-eng.htm |

| ↑6 | Health Officers Council of British Columbia. (2005). A Public Health Approach to Drug Control in Canada. Retrieved from: http://www.cfdp.ca/bchoc.pdf |

| ↑8 | Hari, Johann. (2015). Chasing the Scream. The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs. New York: Bloomsbury. |

| ↑9 | Maté, G. (2008). In the realm of hungry ghosts: close encounters with addiction. Toronto: Random House. |

| ↑10 | Thomas, G. (2005) Harm Reduction Policies and Programs Involved for Persons Involved in the Criminal Justice System. Ottawa: Canadian Centre on Substance Use |

| ↑11 | Erickson et. al. (2002) Center for Addiction and Mental Health and Harm Reduction. A Background Paper on its Meaning and Application for Substance use Issues. Retrieved from: http://www.camh.ca/en/hospital/about_camh/influencing_public_policy/public_policy_submissions/harm |

| ↑12 | Pires, R. et. Al. (2007). Engaging users, Reducing Harms. Collaborative Research Exploring the Practices and Results of Harm Reduction. United Way Report. Retrieved from: |

| ↑13 | Bierness, D. (2008) Harm Reduction: What’s in a name? Canadian Center on Substance Abuse National Policy Working Group. Retrieved from: http://www.ccsa.ca/Resource%20Library/ccsa0115302008e.pdf |

| ↑14 | Neilson, A. & Bridgstock, B. (2017). Addressing emerging mental health and addiction needs in post-secondary institutions. Algonquin College Student Support Services. Retrieved from: http://www.addictionsandmentalhealthontario.ca/uploads/1/8/6/3/18638346/hp6_-_addressing_emerging_adult_mental_health___addiction_needs_in_post-secondary_institutions.pdf |

| ↑15 | Smith, J.L. et al. (2014). Deficits in behavioural inhibition in substance abuse and addiction: A meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend, 145:1–33. |

| ↑16 | Stanis, J. J. & Andersen, S. L. (2014). Reducing substance use during adolescence: A translational framework for prevention. Psychopharmacology, 231, 1437–1453. |

| ↑17 | National College Health Assessment. (Spring 2016). Ontario Canada Reference Group: Executive Summary. Retrieved from: http://oucha.ca/pdf/2016_NCHA-II_WEB_SPRING_2016_ONTARIO_CANADA_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf |